Card

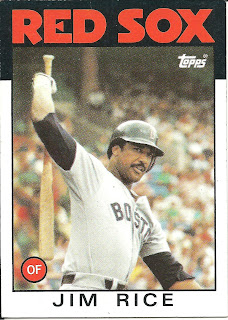

thoughts: An in-action shot on deck. Not often

you see one of those, but a nice “quiet moment” in a game picture.

The

player: You can make the case that Jim Rice has

benefited as much as Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens from steroids. In his case,

his borderline Hall of Fame power numbers looked pretty unimpressive when

stacked against sluggers in the steroid era. But voters had to vote for someone

to put in the Hall, and they had already sent in the obvious hitting stars of

the 80s: (Mike Schmidt, George Brett, and um Kirby Puckett?). So

Rice was chosen for the Hall in 2008, despite having numbers similar to Andres

Galarraga and Carlos Lee.

Known as “Ed” growing up in the segregated south, he

was one of the first African-Americans to attend a previous all white high

school in Anderson, South Carolina. But Jim was not the aggressive type,

despite his size, and his arrival did not seem to cause a lot of racial tension

(well, it was the early 70s and attitudes were changing).

Drafted in the first round by the Red Sox out of

high school, Rice showed a great power stroke at ever minor league stop. The

leagues he played in (New York-Penn, Florida State, and Eastern) are

notoriously pitcher friendly, so the numbers were even more impressive in

context. By the time Rice got to AAA

Pawtucket in 1974, it was clear he was ready for the majors as he won the

Triple Crown and MVP awards at that level.

In his first year as a regular (1975), Rice barely

missed a step clubbing 22 home runs and driving in over 100 en route to a

second place Rookie of the Year showing (his teammate #55 Fred Lynn won the

award, in what must have been the best rookie outfield duo in history).

Unfortunately for the Red Sox, a Vern Ruhle pitch broke his hand near the end

of the season, keeping him out of the World Series. It took awhile for the hand

to heal, and Rice endured a sophomore slump (although hitting 25 homers and driving

in 85 is still pretty impressive). But that season highlighted Rice’s only

weakness, as he led the league in strikeouts with 125. The other weakness was

his lack of patience. Despite being a slugger, Rice generally only walked 50

times or less a season.

The lack of patience didn’t seem to affect him

during a remarkable three year stretch (1977-1979) in which he led the league

in total bases each time (a feat that hadn’t been accomplished since Ty Cobb)

and won the MVP award in 1978, when the led the league in hits (213), triples

(15), home runs (46), runs batted in (139), slugging (.600) and OPS (.970).

After that remarkable three year runs, Rice’s hand

was injured again in 1980, leading to three straight years or good, not great,

power numbers. However, in 1982 he might have saved a young boys life. A

toddler was hit in the head by a foul ball, on Rice, in the on deck circle,

leapt into the stands and carried him into the Red Sox club house to be seen by

the team trainer.

1983 was a renaissance year for Rice, as he once

again led the league in home runs (39) and RBIs (126) while hitting .305. Three

more years of over 100 RBIs followed, but on the bad side, Rice was grounding

into over 30 double plays a year (with a record 36 in 1984), one of the reasons

that pitchers were so apt to pitch to the dangerous Rice with people on base.

After his last season with 200 hits (1986), Rice

began to slow down. While still a fearsome presence at the plate, he would

never again hit over 20 home runs or drive in over 100. The issue was eyesight,

elbow, and knee problems.

Rice would play his entire 16 year career with the

Red Sox. When he retired, he had 382 home runs, 2,452 hits, and 1,451 runs

batted in with a .502 slugging percentage. His home run total was 10th

best in American League history when he retired.

Rear guard: Two of Rice's home runs were solos; the other drove in fellow Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski.

No comments:

Post a Comment