Card

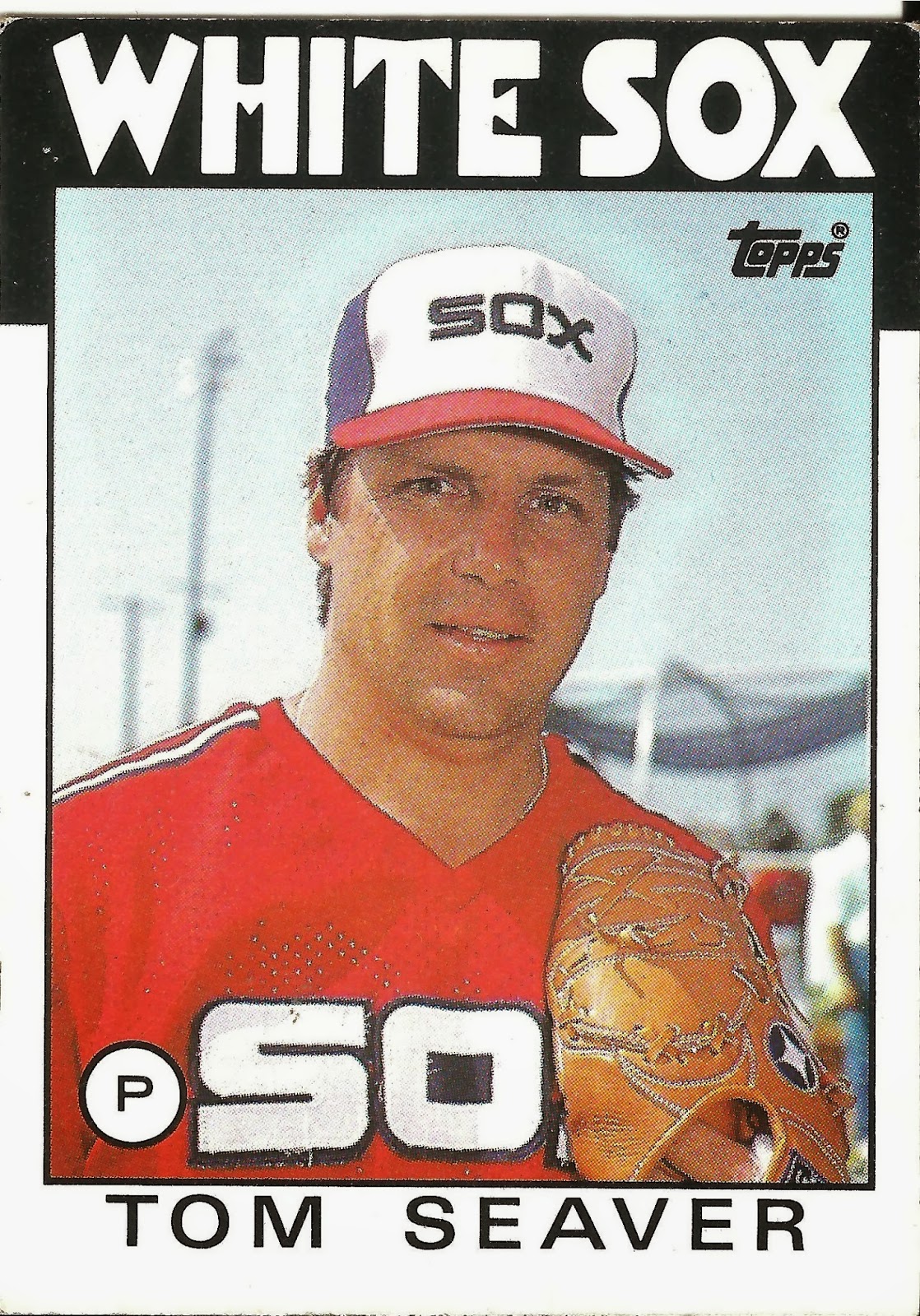

thoughts: Nearly the end of the line here for "Tom Terrific". And it’s too bad that his last card

as a White Sox player shows him in that awful mesh softball jersey they wore in

spring training.

The

player: Tom Seaver was one of the most dominant

pitchers of his era (or any era). Pitching with a classic overhand motion,

Seaver’s fastball touched 95 mph, in an era when that was rare. He supplemented

that with a devastating slider and curve. But Seaver was more than just a power

pitcher. From a very early age, he knew how to set up hitters. The ability of

Seaver to hit his spots with uncanny consistency for such a long time (he was

the league leader in wins at age 36), made him an easy first ballot Hall of

Famer (in fact, his 98.8% voting percentage is the highest in Hall of Fame

history).

A star pitcher at USC, Seaver was involved in a

curious contract dispute before his career even began. The Atlanta Braves

illegally signed Seaver while the college season was still in progress. The

commissioner’s office voided the contract, and conducted a lottery of Seaver,

with just three teams, the Indians, Phillies, and Mets, willing to match the

Braves’ signing bonus. The Mets won, and it was just like winning the real

“lottery.” Seaver spent just one year in the minors at Jacksonville before becoming

a major league star in 1967.

The Mets at that time were a terrible team, but they

had a lot of good young pitching. Seaver went 16-13 as a rookie (for a tenth

place team), winning Rookie of the Year honors. He also pitched in the first of

seven straight all star games, this time earning a win.

1968 was another year where Seaver had a miniscule

ERA (2.20), but a barely above .500 win loss record (16-12). That would all

change in 1969. As the ace of the Miracle Mets, he finally had a decent offense

behind him, as he led the league in wins (25), earning the Cy Young Award in

the process.

Picked the pitch the first game of the NLCS, Seaver

was bombed by the Braves for five runs in eight innings. He fared a bit better

in the World Series, winning 1 and losing 1. There was a rumor going around

that if the Mets won the World Series, Seaver was going to put an ad in the New

York Times denouncing the Vietnam War, which he said was unfounded. His

picture, however, was used (unauthorized) for Moratorium Day flyers handed out

before Game 4.

Seaver became even more dominant in the early 70s.

Learning to harness his control, he routinely led the league in ERA (1970,

1971, 1973) and strikeouts (the same years). He even got a chance to go back to

the World Series in 1973, but the Mets lost to the A’s. Seaver pitched well as

always, but the weak Mets offense failed to back him up (his losses in the

post-season: 2-1 to the Reds and 3-1 to the A’s). For his regular season work,

Seaver would earn his second Cy Young Award, the first awarded to a player who

had failed to win 20 games (he won 19).

A sore shoulder that Seaver had developed near the

end of the 1973 season (perhaps due to seven straight years of pitching over

250 innings) limited his effectiveness in 1974. His 11-11 record, 208 innings

pitched, and 3.20 ERA were all career worst numbers. Considered the clubhouse

leader of the Mets (and a franchise player), rumblings appeared in the press

that Seaver was becoming a surly, malcontent. But he didn’t let the press get

to him and 1975 was a bounce back year, as Seaver led the league in wins (22)

for the first time since 1969, once again earning the Cy Young Award.

Although his win total dropped in 1976 (14), his

league leading 235 strikeouts marked the ninth straight year he had topped 200

strikeouts (this was a record at the time). But changes were coming to

baseball. Free agency had tentatively began, and Seaver wanted a big contract

which the Mets owner was loathe to give out. Instead, he signed an incentive

laden contract, which led to friction between him and the front office. This

was the background for what is considered the worst trade in Mets history.

After previously threatening to trade him for #335 Don Sutton (not too bad of a trade, considering who he was actually traded for),

the Mets finally pulled the trigger in 1977. Seaver was being jerked around by

both management and the press, and he was sick of it, refusing to sign a deal

he had (in principle) extending his contract, and remaining a Met. He demanded

a trade, and, without leverage, the Mets made a bad one, sending Seaver to the

Reds for a bunch of young players, none of which turned out to be much good.

With the trade, there seemed to be a load lifted off

Seaver as he went 14-3 the rest of the way with a 2.34 ERA. But although he was

still an “ace”, it was inevitable that Seaver began to slow down as he

approached his mid-30s. Although he still had effective years for the Reds,

only once was his arm strong enough to put them in the post season (1979).

Although he had a renaissance year in 1981 leading the league in wins (14), his

shoulder problems surfaced, and his 5-13 record in 1982 showed Seaver’s age.

The Big Red Machine was aging as well, and the team needed to turn over a new

leaf.

So the Reds sent him back to the Mets for a

homecoming of sorts. As the Opening Day starter, Seaver drew 48,000 fans to

Shea Stadium for a franchise that had become moribund since the trade of

Seaver. But he had another sub par year at 9-14, a looked to be done at 39. So

the Mets left him “unprotected” which allowed the White Sox to “claim” him

after losing Dennis Lamp to free agency.

Pitching mostly with guile, Seaver won 15 games in

1984 and 16 in 1985 with the White Sox, including win 300 at Yankee Stadium. But the end was near, and after another half season with the

White Sox, he was dealt to the Red Sox for #233 Steve Lyons, where he

finished his career.

If you judge a pitcher by his WAR, Seaver is the

seventh best pitcher of all time (JAWS says sixth). Besides going into the Hall

of Fame in 1992, Seaver has broadcast games for the Yankees and the Mets, and

now runs a winery

in California that produces a small batch of Cabernet Sauvignon. He also

recently battled

a bad case of lyme disease, which he thought was early onset

dementia.

Rear guard: One thing that sucks about these long careers is that the small print makes it really hard to see what categories Seaver led the league in (always my go to when I was young to assess whether the card was any good).