Card thoughts: Rick Miller is not a pitcher, although he looks like he’s warming up

one in the bullpen before a game.

The player: Rick Miller was on a team

for one reason: His defense. Although he hit righthanders well enough to be

platooned occasionally, his real value was as fourth outfielder who you could

count on not to blow the big play.

Miller won a basketball

scholarship to Michigan

State

Playing more in 1973, usually

backing up Tommy Harper in center, he hit just .214. Slated for the same role

in 1974, injuries to Reggie Smith, and lackluster play by #60 Dwight Evans,

allowed Miller to get into 143 games (a career high) and steal 12 bases. Miller

also married #290 CarltonFisk’s sister after the season.

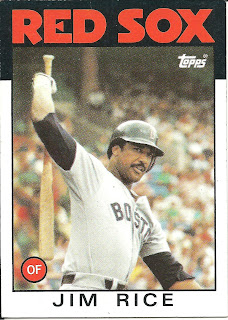

The next 3 seasons saw

Miller’s playing time decline, as youngsters Jim Rice and Fred Lynn needed less

defensive backup than their forbears. In addition, they rarely came out of the

lineup, meaning Miller had to be content in a pinch hitting role. The low point

in his career was in 1975, when he hit just .194. While his number rebounded

some the following seasons, it looked like his days as a regular player were

over.

But then came free agency,

and the owners didn’t really know how to lavish their money in those days. For

some reason, the Angels chose to sign Rick Miller, a 30 year old reserve

outfielder as their starting centerfielder after the 1977 season. As the team’s

leadoff hitter, he hit .263, with an on base percentage of .341. On the other

hand he was caught stealing 13 times, while stealing just 3 bases. But in the

field, he was as good as ever, winning the Gold Glove.

1979 was Miller’s best year,

as he hit .291 in the regular season, and .250 in the ALCS. After another year

with the Angels, Miller came back to the Red Sox, this time as their starting

center fielder. But as he was always a stopgap solution, Miller was perpetually

in danger of losing his job when someone better came around. This time, it was #255 Tony Armas in 1984.

The rest of his career was

uneventful on the field, as he mostly pinch hit. But in his last season,

Miller ended up going after some fans in the stands in Anaheim after they spent the game

heckling his family.

Rear guard: Miller's 1,000th hit came off the Angels' Ken Forsch, and was a pinch hit double (Miller was pinch hitting for #35 Glenn Hoffman). Furthermore, the hit score the first run of the game in the eighth inning. Unfortunately, Miller was thrown out at the plate by Gary Pettis while attempting to score on a single to center by Jerry Remy. The Red Sox could have used that run as Bob Stanley couldn't hold the lead in the ninth,