Card

thoughts: On the verge of one of the most

spectacular rookie seasons ever, I remember just being completely afraid,

everytime Coleman was on base. You just knew he’d steal at least second (and

probably third), and no one was going to catch him. Think: Billy Hamilton

The

player:

What is it about champion base stealers? Like Rickey Henderson,

Coleman’s arrogance eventually alienated many of his teammates. Unlike Rickey,

he didn‘t have the all-around talent to back up his lofty pronouncements of his talent.

Coleman began setting base stealing records in

college, and he continued while in the minors. Despite missing a month with a

broken hand, Coleman stole an incredible 145 bases at Macon (South Atlantic

League) in 113 games in 1983, which was the minor league record before Billy Hamilton

broke it a year ago. He stole another 101 bases at Louisville, as he bounced up

two and half levels in 1984.

Coleman came up with the Cardinals when Tito Landrum

was injured early in 1985, and he immediately started stealing up a storm,

ending up with a rookie record 110 steals (and the third highest total in major

league history). Coleman was a perfect fit for spacious, astroturfed Busch

Stadium, although, despite his great speed, he wasn't much of a left fielder.

However, there were some bumps on the way to his

unanimous selection as Rookie of the Year. When he was compared to Jackie Robinson, he claimed not to know

who he was. And the speed masked the fact that Coleman was just an average hitter,

who didn’t walk much for a guy with no power (his 115 strikeouts were sixth in

the league).

Another pitfall that was not Coleman’s fault

occurred when he was stretching in the outfield during the NLCS. While he was

stretching, the automatic tarp unrolling machine started up, and rolled over

his leg, incapacitating him for the World Series. Tito Landrum, Coleman’s

replacement, hit .360 in the series, but they missed his speed.

Coleman would go on to lead the league in steals for

all six seasons he was with the Cardinals, including having over 100 steals in

each of his first three seasons. He finally made the all star team in both 1989

and 1990. A highlight of this period was Coleman’s 50 straight steals in 1990.

As one of the top leadoff men in baseball, Coleman

was highly sought after when he declared free agency after the 1990 season. He

eventually signed a four-year contract with the Mets. The Mets were in their

most dysfunction phase in the early 90s, with former stars #250 Dwight Gooden

and #80 Daryl Strawberry dealing with substance abuse issues and injuries.

Unfortunately, the addition of Coleman added to this dysfunction (although he

did replace Strawberry). A myriad of injuries kept Coleman from playing in more

than 100 games in any of the years for played for the Mets. Even worse, leg

injuries sapped his speed, which was his only plus tool. When Coleman was on

the field, he caused a myriad of problems including:

--Ignoring coaches’ steal signals on the basepaths

--Fighting with coach Mike Cubbage (and thereby

showing up manager Bud Harrelson) when he hit out of order in batting practice

--Claiming that the poor playing surface at Shea

Stadium was keeping him out of the Hall of Fame (since he couldn’t steal)

--Recklessly swinging a golf club in the Mets

clubhouse, injuring Dwight Gooden’s arm

--And most notoriously, hurling a firecracker into a

crowd of autograph seekers at Dodger Stadium, injuring three people including a

little girl.

Tiring of Coleman’s antics, the Mets sent him to the

Royals in 1994 for way more than they should have gotten, slugger Kevin

McReynolds. Although he was able to play in more games with the Royals, and

stole 50 bases, Coleman was now viewed as damaged goods, a mercurial, arrogant

player prone to injury. He did seem to clean up his act once he got to Kansas

City, but he was on the move often in his last few years in baseball, going

from the Royals, to the Mariners, to the Tigers, and to the Reds as little more

than a backup outfielder. He ended his career at AAA Louisville in 1998 when he

didn’t get called up by the Cardinals.

Despite his career as a regular basically being over

at age 28, Coleman still ranks sixth all-time in stolen bases, and had a

remarkable career steal rate of 80%. Since retirement, he has been a minor league

base stealing instructor for the Cubs and other teams.

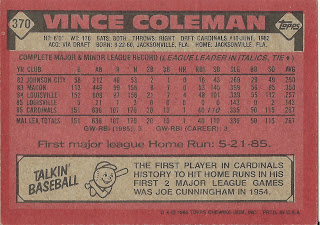

Rear guard: Coleman would only hit 28 career home runs, and his first was an inside-the-park home run off #24 Len Barker.

Everyone knows about Joe Cunningham right? Well, Joe seemed like a good prospect, but he never really panned out. He only hit 9 more home runs the rest of 1954, and only 64 over a 12-year career with the Cardinals, White Sox, and Senators. Here's his "collage" card from 1955.