Card

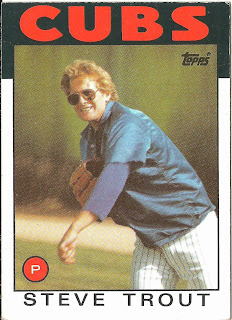

thoughts: Trout looks like a paunchy middle aged fantasy

camp participant in this picture, as there is little to show that he’s an

actual baseball player (save the striped pants). This was not the only card

where Trout sported his poodle-fro to the fullest: He looks particularly hesher

on his 1981

Topps card.

The

player: Trout one of those guys that lazy

broadcasters (like Joe Buck) like to describe in shorthand as a “flaky” lefty. Maybe

flaky because the guy spouts things other than sports clichés when quizzed

after games in the clubhouse, or perhaps because his nickname is “Rainbow.” Or

maybe it was because he would challenge teammates to burrito eating contests

when they were on the West Coast.

A local boy who had the luck to play with both

Chicago teams (Don Pall and Phil Cavaretta are the only other local players I can recall who did that), Trout was the son

of famed starter Dizzy Trout, who won 170 games, mostly with the Tigers. Not

only that, his grandfather worked for Bill Veeck, who owned both the Cubs and

the White Sox 9although not at the same time).

As was the custom of the time, Trout “apprenticed”

his first full year in the majors as both a starter and a reliever, having more

success in the former role (10-6, 1.45 strikeout-to-walk ratio as a starter)

than the latter. Given a more substantial role in 1980, he foundered, ranking

fourth in the league in losses (16) and leading in hit barters (9).

A couple of mediocre years followed, with Trout

ineffective due to injury and increasing wildness. The White Sox finally gave

up on him after the 1982 season, completing a rare big trade with their

crosstown rival Cubs, with #187 Scott Fletcher, Pat Tabler, Randy Martz, and

Dick Tidrow going the other direction.

While Trout’s first season with the Cubs was

unmemorable (except for his notable disdain for signing autographs), he was a

key part of the Cubs pennant drive in 1984 when he, like many players on that

team, had a career year, going 13-7 with a 3.41 ERA. He continued his strong

pitching in the division series, winning Game 2.

Trout started strong in 1985, but a nerve condition

in shoulder sent him to the DL—along with what was basically the rest of the

starting rotation—for half of the season. Although he had a winning record and

low ERA (3.39), storm clouds were ahead. Trout for the first time walked more

(63) than he struck out (44), a curse that would plague him the rest of his

career. Trout ‘s alarming increase in wildness was upping his pitch count so

much, he was having a hard time going deep into his starts. So much so, that he

was bounced from the rotation in the middle of the following year.

It seemed, however, that Trout was making a comeback

in 1987. He started strong once again, going 6-3 with a 3.00 ERA. His last two

starts with the Cubs were shutouts, before he was traded to the Yankees for three

young pitchers who never did squat for the Cubs (although Bob Tewksbury went on

to have a flukily good couple of years with the Cardinals in the early 90s).

With the Yankees, his control problems returned with

a vengeance. In just 46 1/3 innings, Trout threw 9 wild pitches and walked 37.

He couldn’t get past the sixth inning in any of his 9 starts.

Feeling burned, the Yanks essentially paid for Trout

to go away, sending him to the Mariners with a cool million for three more

young pitchers. The Seattle team foolishly elected to make Trout their Number 2

starter, and his first start for the team (2/3 of an inning pitched, 5 walks, 2

wild pitches) was an prelude to the rest of his season (31 walks, 7 balks(!),

and 5 wild pitches in 56 1/3 innings with an ERA over 7).

Trout barely pitched in ’89 (and badly at that),

before being released in June for good. In retirement, he’s managed a baseball

camp, done some indy league coaching, and once coached a high school baseball

team in Hawaii after answering an ad in the paper.

He still lives in the Chicago area (and has a very

Rainbow-brite looking Website),

and oddly enough the site lists his home address (a tiny bungalow in a working

class area of Hammond, IN), so maybe Trout will sign your autograph now that

he’s retired.

Rear guard: Chick Tolson was a mighty minor league slugger (career slugging percentage: .621) who found it hard to crack the lineup during a time when Cubs teams regularly hit above .280. His grand slam came off Pirates starter Ray Kermer, and he was pinch hitting for long forgotten reliever Percy Jones. Tolson would hit just 4 home runs in a 5 year career.