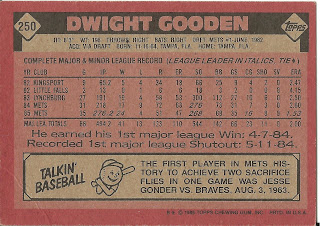

Card thoughts: As a batter this season, this was the most fearsome thing you could ever imagine. Dwight Gooden, about to hurl a pitch--most likely past you. Much better shot than one taken as

a rookie in the dark.

The player: As a kid, I saw Gooden throw a gem against the Cubs at Wrigley. He struck out a ton of guys, and I doubt if the Cubs even scored off him. Gooden, or "Doctor K" as he was known in his prime, was one of the most exciting young pitchers ever, comparable to Bob Feller and Kerry Wood in his success at a very young age. But with that success came a price. A heavy workload as a youngster ruined his arm, and he did not handle the early fame well, ending up as a drug addict within a few years. He truly went, as the Sports Illustrated cover story said, from phenom to phantom.

But for a three year period, before he was even 21 years old, Gooden dominated like few other pitchers in history. Featuring a nasty curve and n almost unhittable fastball, he made his first start at age 19 in 1984, and he went 17-9 with a 2.60 ERA, leading the league with 276 strikeouts, and easily winning the Rookie of the Year, nearly winning the Cy Young Award, and making the all star team where he struck out the side.

It was only a taste, however, of one of the most thoroughly dominating pitching seasons in baseball history. When this card was issued, Gooden was coming off a year when he would win the pitching equivalent of the Triple Crown. His league leading 1.53 ERA was second lowest in the "live ball" era (Gibson's 1.12 in the dead ball year of 1968 holds the record), he struck out 268 batters, won 24 games (completing 16), and pitched 276 2/3 innings---leading the league in all categories. It still wasn't enough to propel the Mets into the playoffs, however.

Gooden's numbers fell off a bit in 1986, as he went 17-9 with a 2.84 ERA. He did become the youngest pitcher to start an all star game at age 21. He didn't pitch well, however, giving up 2 runs in 3 innings and getting the loss. Gooden was good in the ALCS that year, but couldn't make it out of the fifth inning in any of his World Series starts, an indication that the amount of innings on Gooden's young arm was beginning to effect his performance. Another warning sign was that he missed the Mets victory parade. This was because he was too hungover after going on an all night cocaine and alcohol bender. Gooden ended up watching the game on TV at his dealer's apartment.

Gooden's cocaine troubles came to the surface in the off-season when he was arrested for the first, of many times, DWI by the Tampa police. He still did lots of cocaine all off-season, and he was suspended in spring training when it was found in his system. Gooden managed to start 25 games and go 15-7 with a respectable 3.21 ERA. The 1988 season would be a comeback year, as he went 18-9, made the all-star team, and pitch over 200 innings.

After an injury to his shoulder in 1989 limited him to 17 starts, Gooden would have one last dominant season, going 19-7 and 223 strikeouts, second n the league. Another injury in 1991 finished out the dominant period of Gooden's career. Although he went 13-7, he no longer could strikeout almost a batter an inning, and his walks and ERA climbed. a 10-13 and 12-15 record got the Mets in the subsequent two seasons led many to conclude that Gooden was done. And his behavior became more erratic. Testing positive twice for cocaine in 1994, he only made 7 starts that year, and was suspended the following season after again testing postive during his first suspension. During this time, Gooden attempted suicide.

Gooden was not resigned by the Mets, and George Steinbrenner who, whatever his faults, was always willing to give "damaged goods" another changed, signed him to pitch for the Yankees in 1996. He managed to go 11-7, and even

no-hit the Mariners on May 14. But he had to be shut down at the end of the season because of arm fatigue, and his ERA was an awful 5.01.

Another mediocre season with the Yankees followed, and Gooden started for the Indians in 1998 and 1999, and pitched for the Astros, Devil Rays, and Yankees in 2000. He ended his career, mopping up in two playoff games for the Yankees.

Despite all of the troubles, Gooden ended up pitching 16 seasons. He won over 100 games by the age of 25, and only 75 after, finishing with a career record of 194-112. What could have been.

As you can probably guess, Gooden's alcohol and drug problems became even worse after his retirement, without the structure of baseball to rein him in. He even chose to go to jail for a time to kick his habits, but to no avail. If you are one of those sick people

who enjoy watching the suffering of others, you can catch Gooden on the 2011 season of Celebrity Rehab.

Rear guard: Look at that. His first shutout was only a month after his first win. Gooden pitched a 4-hitter, striking out 11 in a duel against the Dodger great Fernando Valenzuela.

Ooh! 2 sacrifice flies in one game! Now I know for most of the Mets history they were seen as a kind of a loser franchise, but they did win in '69. Give em a break with the pathetic stats! Jesse Gonder (shown here on

his 1964 card), was a backup catcher the Mets acquired in July for Charlie Neal and Sammy Taylor (sent to the Reds). He had only 6 sacrifice flies in his career, and his 2 in that August game were his only 2 of the year. They drove in Duke Snider with the Mets' fourth run, and Ron Hunt with the sixth.

This date in baseball history: Well, whaddya know. Our featured attraction, Dwight Gooden, strikes out 16 Phillies in 1984 to set a two game strikeout record.