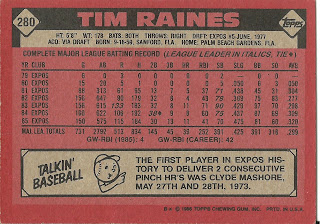

Card thoughts: Raines in all of his Jeri-curl glory, apparently with both an elbow injury and an "owie" on his left forearm. Seeing this card reminds me of the weird “Rock Raines” card that appeared in 1989 Topps packs. Why would you call a guy Tim on every other card, and call him “Rock” on this one? I thought he was Tim Raines’ brother!

The

player: For many years, Raines was the National

League equivalent of Rickey Henderson. A short man (like Henderson), he could run, hit for

power, was patient, and was the best leadoff hitter in the National League for

over a decade. Yet, Raines still gets shafted for the Hall of Fame, despite the

fact that great leadoff hitters are rarer than great power hitters, and few

teams even have a good consistent leadoff hitter.

Raines came up as part of a talented core of young Expo

hitters in the early 80s that included Hall of Famers #170 Gary Carter and

Andre Dawson, as well as forgotten mashers like Warren Cromartie and Tim

Wallach. While Raines didn’t have the slugging prowess of those hitters, boy,

could he run. After two small cups of coffee in 1979 (3 runs scored as a pinch runner,

no at bats) and 1980 (1 for 20, 5 runs scored), he finally made the bigs for

good in 1981, and likely would have stolen over 100 bases had the season not

been interrupted by a strike. As it was, he stole 71 bases (leading the

league), then a record for a rookie (since broken by #201 Vince Coleman). But

that was also the year of

“Fernandomania,” so he was denied the Rookie of the Year award.

His career, however, almost was derailed by rampant

cocaine abuse in 1982. He would use the drug constantly, reportedly spending

over $40,000 (in today’s dollars: $95,000) on it for the season. In a somewhat

legendary story, Raines would always slide head first in bases in order to not

break a glass vial of coke he kept in his back pocket for use during games.

Raines would steal at least 70 bases until 1986,

making the all-star team each year and leading the league in steals for 4

straight seasons. There were other aspects to his game as well during this

period of dominance. He hit for a high average, but also consistently walked

while minimizing his strikeouts. Despite mostly having doubles power (Raines

led the league in that category in 1984), his OPS consistently topped .800, due

to this penchant.

In his peak years (roughly: 1981-1987), Raines also

led the league in runs twice (133 in 1983; 123 in 1987), and batting average

and on-base percentage in 1986. With the arrival of Vince Coleman in 1985, the

days of Raines being a steal champion were over, although he would steal at

least 10 bases a year for another decade.

Despite Raines star status, he mysteriously was not

signed when he became a free agent in 1986. Of course, it was later determined

that the owners were engaged in collusion to keep salaries low in that off

season. He was later forced to sign with the Expos a month into the 1987

season. Despite having had no spring training, he dominated his first game back

going 4 for 5 a triple and a game winning grand slam. Another highlight of that

season was winning the all-star game MVP when he hit a game-winning triple in the thirteenth inning.

Although Raines would remain a valuable leadoff

hitter after 1987, he would never again be a major star, and that all-star game

would be his last. In 1990, he was traded to the White Sox, with the main

player going the other way being Ivan Calderon.

Raines scored over 100 runs in each of his first two seasons with the

Sox, the first time he had done so since in three years. But all those years on

the artificial surface in Montreal had done a number on his legs, and he

struggled to stay on the field the next two seasons. In 1995, Raines would play in over 130 games

for the last time, and his .285/.374/.422 was pretty good, but he stole only 13

bases (however from 1993-1995 he had stolen 40 straight bases, a record at the

time).

On to the Yankees next, Raines was their fourth outfielder

the next three seasons. After a 58 game stint with the A’s in 1999 where he hit

.215, it was thought his career was done when he contracted lupus. But after a

year out of the majors, he came back in 2001 with the Expos. In a severely

limited role, he managed an .862 OPS in 89 at bats. Near the end of the season,

he was traded to the Orioles so he could play the outfield with his son, Tim

Raines Jr., the second time in history that had occurred (the other being the

Griffeys). After a year with the Marlins where he mainly was a pinch runner

(despite stealing 0 bases) and occasional pinch hitter (.191 average), Raines

retired.

For his career, statistics that just scream hall of

fame include being fourth all time in stolen bases (808) despite only being

caught about 15% of the time. He also had over 1,500 runs scored and over 2,600

hits. He is most comparable to Lou Brock. Despite this, Raines has still not

gotten over 50% of the Hall of Fame votes. There are several more exhaustive

cases for Raines being in the Hall of Fame (Bill James

calls him the second best leadoff hitter ever).

Post retirement, Raines coached in the majors from 2004-2006,

generally at first base, most memorably with the White Sox 2005 World Series

Championship season. Since then, he has managed and coached in both affiliated

and independent minor league ball.

His son, Damon Mashore, was a reserve outfielder for the Angels and A's from 1996 to 1998.