Thursday, April 26, 2012

#205 Record Breaker: Tony Perez

Card thoughts: Interesting how some of the best in-action shots so far are for these record breakers. This is not a picture of the actual grand slam, however.

The record: Wow, this one had stood for awhile. The record was set by Cap Anson in 1984. It has since been broken by Julio Franco.

Rear guard: Perez was pinch hitting for starter John Stuper. His grand slam drove in #195 Dave Concepcion, Ron Oester, and #143 Dave Van Gorder.

This date in baseball history: Harry Chiti is traded to the Mets for a player to be named later in 1962. Chiti ends up being the player to be named later when he sent back a month later.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

#204 Record Breaker: Phil Niekro

Card thoughts: No doubt, Niekro is about to throw a knuckler.

The record: That shutout was Niekro's last. 1985 would be his last season with a winning record as well.

Rear guard: Satchel Paige was so old because he had to play in the Negro Leagues for so long. The year he set the record, he was used mostly as a reliever. Niekro's record breaking shutout was on the final day of the season. He walked 3 and struck out 5. Niekro would end up pitching until he was 48.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

#203 Record Breaker: Keith Hernandez

Card thoughts: If Hernandez is driving in a run here, he's doing it very awkwardly. How often do you see a batter swing and have his helmet come off?

The record: Since the game winning RBI is a meaningless statistic only tallied between 1980 and 1988, it's hard to get too excited about this feat. If it means anything to you, Hernandez also holds the all time record with 129.

Rear guard: Only in New York City do neighborhoods get their own "specific" address i.e. Flushing.

Monday, April 23, 2012

#202 Record Breaker: Dwight Gooden

Card thoughts: This is a nice illustration of Gooden’s pitching motion on what looks to be a gloomy day at Shea. His base card is a frontal shot of him pitching in spring training.

The record:

The reason why some baseball records are split into the “modern” and “all-time”

is that the statistical rules varied widely in the 19th century. Willie

McGill, who won 21 games at age 17 for Cincinnati

and St. Louis

of the American Association, holds the all-time record. Due to babying these

days of young pitchers, and the more frequent use of the bullpen, Gooden’s

record is unlikely to be broken any time soon.

This date in baseball history: Joe Morgan's record 91 errorless game streak at second comes to an end in 1978. The record would be broken by Ryne Sandberg and later Placido Polanco.

Sunday, April 22, 2012

#201 Record Breaker: Vince Coleman

Card thoughts: Coleman is not stealing a base in this picture. He's following the ball as he runs to third. As usual with the Record Breaker cards, the photo is more interesting than the base card.

The record: This is going to be a record that stand for a long time, perhaps the rest of my life. With the gradual elimination of artificial turf, it's tougher for players, even greatest base stealers, to get the great jumps they used to back in the 1980s. Generally, you can lead the league with about 60 or 70 steals these days.

Rear guard: Vincent Van Go is one of the all time most terrible nicknames. It is worth noting that Coleman only broke a one year old record--but did it by 38 steals.The all time season stolen base record is held by Hugh Nicol of the Cincinatti Red Stockings of the old American Association. He stole 138 bases in 1887.

This date in baseball history: In one of the all time futile pitching performances, 4 Kansas City A's pitchers gave up 11 runs in one inning to the White Sox while only allowing one hit. 2 errors, 10 walks, and one hits batsman were the culprit. An incredible 8 runs scored after being walked in.

Thursday, April 19, 2012

#200 Mike Schmidt

The last 100 cards stats:

Head shots: 6%

Candid shots: 32%

Action Shots: 34%

Posed shots: 28%

Mustaches: 22%

Glasses: 6%

The most read post 100-200? Wally Backman. He has also supplanted Steve Yeager as the most popular 1986 Topps blog player.

Card thoughts: The best third baseman of all time should not have to wear his pajamas to the plate. This is the only Schmidt Topps card to show him playing any position other than third.

The player:

548 home runs, including some of the longest in his generation; three MVP

awards (including 2 straight); 12 all star appearances; 9 straight gold gloves

(and 10 overall): Schmidt was the definition of the complete player. His only

flaw was his propensity for strikeouts (9th all time) and inability

to hit for average (.267 lifetime). He’s considered the greatest Phillie of

all-time.

Schmidt began in the minors as a shortstop, but was named

the Phillies starting third baseman in 1973. He probably wasn’t quite ready for

the majors yet. He hit only .196 with 136 strikeouts in only 367 at bats. But

he figured it out pretty quick the following season when he hit 36 home runs

and slugged .548 to lead the league. He also led in strikeouts. The next three

seasons he would lead in both home runs and strikeouts, with a high of 180 in

1975 which was a record at the time.

Schmidt’s prime years were between 1979 and 1987. He hit

more than 30 home runs every single one of those years, even in 1981 when he

had only 354 at bats. The explanation for Schmidt’s increased success is the

reduction of his number of strikeouts. Highlights included breaking Chuck Klein’s team

record for home runs (45 in 1979); winning the World Series MVP award in 1980;

and winning the MVP award three different times, including twice in a row (1980

and 1981).

Schmidt did this all despite chronic knee problems, which

were aggravated by the amount of games played on Astroturf (including his home

field, Veterans Stadium). To help protect his knees, Schmidt was moved by the

Phillies to first base for the season shown on this card. The experiment lasted

only one season, and he was shifted back to third for the rest of his career.

Schmidt surprised many people for announcing his retirement after

a slow start in 1989. He retired, effective immediately, on May 29 in a tearful farewell

address at his locker before a game against the Padres. This is refreshing as

compared to the Chipper Jones model of taking a victory lap around the league.

For the record, Schmidt’s last game was the day before against the Giants. He

went 0 for 3, but walked 2 times.

Schmidt retired with top 20 career totals in home runs

(548); WAR for position players (108.3); sacrifice flies (108); assists as a

third baseman (5,045); and range factor as a third baseman (3.14), among

others. He has largely stayed out of the limelight since his retirement,

although some people believe he and Joe Morgan, as members of the hall of fame

selection committee, were largely responsible for the inability to elect

deserving veterans into the hall of fame the past several years.

Rear guard: For Schmidt, 1985 was a typical year where he belted over 30 home runs, drove in over 90, and slugged above .500. One notable statistic is the 30+ doubles he hit. With all his power, SChmidt had only done that twice before.

This date in baseball history: Crosley Field, a beautiful old ballpark in Cincinnati, was begun to be demolished in 1972.

Monday, April 16, 2012

#199 Dick Howser

Card thoughts: . . . in mid-sentence . . .

The player/manager: Howser was a hotshot young prospect whose career was derailed by injury, as was his managerial career, and, ultimately, his life.

A leadoff hitter with blazing speed and a great batting eye, Howser twice scored over 100 runs: Once as a rookie with the Kansas City A's, again in 1964 for the Angels. These would also be the only years he played more than 100 games. In fact, he managed to play every game in 1964, establishing a record by playing 162 games at shortstop (this record has been tied many times since).

After Howser ended his career with the Yankees in 1968, he immediately moved on to the Yankees coaching staff, where he coached for a decade. After one season off coaching in college, the Yankees brought him back to manage in 1980. He did not disappoint, leading the Yankees to a 100+ win season, and the AL East crown. This did not endear him to irascible boss George Steinbrenner, who was miffed that Howser dared to hang up on him when he called the clubhouse.

Howser was fired after that one season with the Yankees, and the Royals would pick him up the next season. He would manage the rest of his 7 year career with them, never finishing lower than second place. His crowning achievement would be piloting the Royals to their only World Series win, the year shown on this card.

Unfortunately, Howser would not be able to bask in too much glory. While managing in the all-star game in 1986, he kept messing up signals. The cause was a brain tumor, which Howser would battle for another year, before dying in 1987.

Howser does have couple of other lasting legacies: His number 10 was retired by the Royals, and the trophy for the best college player is named after him.

Rear guard: The massive omission here is Danny Jackson, who won 14 games, including a game in the World Series, in 1985. Jackson has Fleer and Donruss cards this year (and in 1984), but no Topps card until the 1987 "Traded" Set. He must have been one of those rare players who did not sign a contract with Topps.

This date in baseball history: Steve Garvey breaks Billy Williams' National League record for consecutive games played with 1,118 games in 1983. The streak will about 90 games later after Garvey dislocates his thumb.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

#198 Ken Dixon

Card thoughts: I really hate those orange rings in the Orioles warm up jackets. They make Dixon look like an extra in a Lost in Space episode. This is Dixon’s rookie card.

The player: Dixon was a promising young pitcher who succumbed to a mysterious shoulder ailment early in his career. Of course, his nickname was also “Dr. Longball,” so his effectiveness was suspect even before the injury.

Dixon really got the Orioles attention in 1984 in AA when he won 16 games and completed all but 9 of his 29 starts. After a cup of coffee that season, Dixon was used as a swing man the season shown on this card. He was fairly effective in both roles, with his lowest ERA at 3.67 and an 8 and 4 record. Dixon was put into the rotation full time in 1986, and despite giving up 33 home runs, he kept the Orioles in most games. His ERA went up bu almost a run and he went 11 and 13. The next season was much worse for Dixon as he was bounced from the rotation after pitching ineffectively. He had a 8-10 win-loss record and an astronomically high 6.43 ERA.

The Orioles traded him after the season to the Mariners for #152 Mike Morgan, but Dixon appeared in spring training with significantly lower velocity, and they released him. It took three years, but calcium deposits on Dixon’s shoulder were the culprit. Famed orthopedic surgeon Dr. James Andrews used his surgery as a test case. Dixon attempted a comeback in 1989, but it didn’t take, especially after he was suspended for refusing to take (or failing) a drug test. He did attempt to become a replacement player during the 1994-1995 players strike by attending the Phillies' spring training camp.

Apparently, the early exit from the game broke Dixon’s heart. And he got in trouble with the law after retirement, including being busted for cocaine possession and accused of stealing a teammate’s traveler's checks. Dixon has now cleaned up, and enthusiastically signs autographs before Orioles games, as well as running a foundation to serve inner-city kids.

Rear guard: Dixon's first major league win came against the Indians. He pitched a complete game, only giving up 1 run on three hits, striking out 6 and walking only 2. Dixon didn't give up the run until the 9th inning, on #59 Andre Thorton's groundout to third.

This date in baseball history: Perhaps hitting the most famous home run in Cubs history, Dave "King Kong" Kingman hits a home run in 1976 that lands 530 feet away from home plate, hitting a house on Kenmore Avenue on the fly.

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

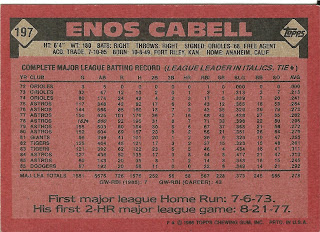

#197 Enos Cabell

Card thoughts: Although my gut says this is Candlestick Park, more likely it is Shea. I can't tell without seeing the color of the walls.

The player: Cabell was very much a player of his time. An average defender at both first and third, he did not hit with the power expected at those positions. Cabell was also notoriously impatient at the plate, leading to few walks. His name has come up recently in connection with Angels' third baseman Mike Trout. It turns out Cabell was the only player since 1950 (before Trout) to become a starting third baseman in the majors with no previous minor league experience there.

Cabell played first, third, and the outfield when he came up with the Orioles in 1972, about the same time as the player in the previous post, #196 Doyle Alexander joined the team. Boog Powell was blocking him at first, so the Orioles shipped him to the Astros in December of 1974. At first, Cabell filled the same utility role as he had on the Orioles, as he was blocked once again at first, this time by Bob Watson. The Astros' solution was to shift him to third, after incumbent third baseman Doug Rader was traded to the Padres.

Although he did not hit with the power expected of a third baseman, Cabell was always decent at getting on with a hit. He had a trio of good years beginning in 1976. His best season was in 1977, when set career highs in runs (101), doubles (36), and home runs (16). Playing every game in the next season, Cabell was 3rd in the league in hits with 195 (which was an Astros record at the time), and placed in the top 10 in runs scored and stolen bases, and led the league in at bats, despite not being a leadoff hitter.

Cabell continued for two more years as the Astros starting third baseman and put up decent, if not spectacular, offensive numbers. A trade after the 1980 season landed him with the Giants, where he moved back to his natural position at first, and exhibited great range.

His time with Giants lasted only one season, and he was traded at the beginning of spring training in 1982 to the Tigers for the awesomely named Champ Summers. Cabell hit the first two home runs of the Tigers season, but hit none after that as he suffered through a weak offensive season. The next year, however, Cabell had his first year of hitting over .300, batting .311. But his power numbers and on on base ability continued to be bad.

Cabell returned to the Astros for the 1984, and part of the 1985 season. His 1984 season was almost identical to the previous one, as his average dropped one point, and his RBIs dropped by 2.

Midway through the season shown on this card, Cabell was traded to the Dodgers, where he actually played more third than first for the first time in several years. Cabell made more news off the field, as he, along with Keith Hernandez, were the two players who named names at the Pittsburgh drug trials. Cabell pretty much used cocaine for almost a decade, getting high with teammates on several teams, as well as opponents, who he named in court. Cabell didn't seem too remorseful for his actions: He stated he always hit better when he was on coke. He was suspended for the entire 1986 season; however, the suspension was declared void since 10% of his salary went to drug prevention programs. Cabell only lasted one more year anyway, hitting .256 in 277 at bats, playing a variety of positions.

Cabell is currently the Astros special assistant.

Cabell is currently the Astros special assistant.

Rear guard: Cabell was busy in the second game of that double header on July 6th: He also stole a base, and was caught stealing. His home run was off of A's star pitcher, Vida Blue.

This date in baseball history: In an inauspicious start for the new New York Mets franchise, the lose to the Cardinals 11-4. They would go on to lose 119 more in 1962.

Monday, April 9, 2012

#196 Doyle Alexander

Card thoughts: That is a very awkward follow through. And mustache.

The player: Alexander was an incredibly inconsistent pitcher, who often pitched his best down the stretch. Once a hard thrower, arm injuries transformed Alexander into a guile pitcher. Other than a mediocre fastball, he threw a curve, change, slider, and sinker from three different arm angles. Besides his reputation as a clutch pitcher, Alexander was involved in two memorable trades, at either end of his career.

Alexander was drafted by the Dodgers in 1968 and was with the club within 3 years. He only lasted the 1971 season before he was traded to the Orioles with three other players for hall of famer Frank Robinson. He began pitching out of the bullpen, but by 1973 he was starting regularly. Alexander was a workhorse, completing 10 out of 26 starts to go with a 12-6 record. He lost his only playoff start.

Two seasons followed, where he bounced between the 'pen and the rotation. It seems the Orioles never knew what to do with him, and they traded him to the Yankees midway through the 1976 season. Alexander pitched much more effectively for them, going 10-5 the rest of the year.

But the Yankees would not enjoy his services long this time. Alexander signed as a free agent with the Rangers the next season, and had his best season to date, going 17-11 with a 3.65 ERA. But much like his time with the Orioles, the subsequent two seasons were marred by injury and sub-.500 records.

Alexander would be traded every year for the next four years. First it was to the Braves (a good season--14 and 11); then to the Giants (double digit wins again, 11 and 7, with a career low 2.89 ERA); then to the Yankees (where he broke his pitching hand punching a wall after being shelled by the Mariners); and finally to the Blue Jays in 1983, where Alexander would have his most consistent success.

Alexander was the top Blue Jay pitcher in both 1984 and the season shown on this card, winning 17 each year, and leading the league in winning percentage in the former year. His success did not translate in the ALCS in 1985, as Alexander gave up 10 runs in about as many innings over 2 starts, losing one of them.

He was traded back to the Braves in the middle of the next season, and he was generally effective with both teams, winning 11 and losing 10. In the offseason, Alexander was one of the free agents blocked by collusion, and therefore did not sign with the Braves until May. He was less than dominant for them, but that Braves team was REALLY terrible. Despite his 5-10 record and above 4 ERA, the Tigers coveted Alexander. He was the kind of big game, stretch run pitcher they needed in their tight race with his old team, the Blue Jays. To get him, they paid a heavy price by trading a minor leaguer named John Smoltz (who went on to win 213 games). Much like the trade of #183 Larry Andersen for Jeff Bagwell, it paid immediate dividends for the Tigers, but at a huge long term loss.

Alexander went an outstanding 9-0 down the stretch with a 1.53 ERA. This did not carry over into the playoffs again, much like in 1985. He lost two starts to the Twins, once again giving up 10 runs. There was a still a last hurrah for Alexander, as he went 14-10 in 1988, to make his first all star team at age 37. But there would be few cheers in his final season, as he led the league in losses with 18, and home runs allowed with 28.

Rear guard: Because of the Topps card issuing policy in 1972, Alexander never appeared as a Dodger, even though he spent the 1971 season with them. Instead, Topps airbrushed him into some semblance of an Orioles uniform.

This date in baseball history: In 1985, Tom Seaver bests Walter Johnson by pitching his 15th opening day.

Sunday, April 8, 2012

#195 Dave Concepcion

Card thoughts: The Reds really had the old Big Red Machine gang back together for one last fling this season: Dave Concepcion was joined by #1 Pete Rose and #85 Tony Perez. Concepcion was the only one of three that never left the Reds.

The player: A case can be made for putting Concepcion in the hall of fame. Before Ozzie Smith, he was the best shortstop in the National League, and was a better hitter. Concepcion was very much of his time: In the days when many parks had artificial turf, he could play deep at short, perfecting throws that bounced on the turf to give him better range. Concepcion played all of his 19 years with the Reds.

Concepcion was only a reserve shortstop the first year the Reds went to the series, in 1970. He did play in 3 World Series games, and hit .333. The next two seasons, Concepcion fielded well, but hit poorly, hitting just above .200 both seasons, while driving in about 20. That all changed in 1973, when he made the first of 9 all star teams. Concepcion's batting average jumped 80 points, and he showed a bit more power.

Concepcion was even better in 1974. Getting into 161 games, he doubled his home run output to 14 and drove in 82 runs. Concepcion also won the first of four straight gold gloves. The next two seasons, the Reds won the World Series and he hit around .280 each year. In the post-season both years, he had his ups and downs, hitting around .400 in one series, and .200 in another.

Concepcion consistently drove in about 60 runs from 1977 to 1981. He had his first .300 campaign in 1978, and a year later had his second power surge, hitting 14 home runs and driving in a career high 86. In 1981, he was 5th in MVP voting. The next year, in his last all star game, Concepcion was the MVP, after hitting a home run to put the NL ahead for good in the second inning.

In 1983, '84, and '85, Concepcion's age began to catch up with him. There were no more .300 seasons, and he began to resemble the light hitting shortstop he had been a decade before. The season shown on this card would be Concepcion's last as a regular shortstop; he would mentor hall of fame shortstop Barry Larkin the remaining three years of his career.

In his final season, Concepcion pitched an inning and a third in a Reds' blowout loss in 1988 giving up 2 hits, striking out 1 (Franklin Stubbs), and giving up no runs.

Concepcion finished his career with the 15th best range at shortstop all time, as well as 2,300 hits.

Rear guard: Concepcion sure had some big ears as a youngster on his first Topps card.

This date in baseball history: In 1974, Hank Aaron passes Babe Ruth as the all time home run king.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

#194 Craig McMurtry

Card thoughts: Here's something you rarely see on a baseball player now: gigantic glasses. Soft contact lenses were still not common in the mid-80s, laser surgery had not yet been invented, and I believe Reds third baseman Chris Sabo was the first to wear prescription sports goggles in baseball, and that was in 1989.

The player: Craig McMurtry won most of the games he would win in his 8-year career in his rookie season. If not for that season, no one would really remember him as a player, even in Atlanta.

Drafted in the first round by the Braves, McMurtry won the International League Pitcher of the Year award while pitching for Richmond in 1982. He won 17 games and had a 3.81 ERA. But, in a worrisome sign, he did this despite walking more (107) than he struck out (96).

McMurtry stormed into the National League in 1983, winning 15 games, losing only 9, with a 3.08 ERA. Only #80 Daryl Strawberry prevented him from winning the Rookie of the Year award, and he came in 7th in Cy Young award voting. The next season, was an absolute disaster for McMurtry as his pitching record was reversed, as he won only 9 games while losing 17, good for 2nd in the league. The problem was his control, as he walked 102 (4th in the league) against 99 strikeouts. The season shown on this card, McMurtry was demoted to Richmond after starting the season 0-3, giving up 36 runs in 45 innings. He righted himself in the minors, going 7-5 with a 3.27 ERA.

In 1986, McMurtry came back up to the majors, where he was ineffective both as a starter and a reliever, going 1-6 with 4.74 ERA. He was then involved in one of the most uninspiring trades of all time, going to the Blue Jays for #45 Damaso Garcia and Luis Leal. Neither McMurtry or Leal would ever play a major league game for their respective clubs, and Garcia only hit .117 for the Braves.

McMurtry was released during the 1987 off season and was signed by the Rangers. He pitched a good chunk of 1988 with the Rangers, where he posted the best ERA of his career with a 2.25 mark over 60-plus innings of relief work. In 1989 and 1990, McMurtry struggled again, shuttling back and forth between Oklahoma City and Dallas. His control problems returned: he walked 30 (with only 14 strikeouts) in 1990.

McMurtry disappeared into AAA for the next three seasons before resurfacing one last time with the Astros, where a 7.74 ERA signaled his future as a player was to be brief.

Rear guard: People sometimes forget that Joe Torre is the rare managerial great who was also a star player. Fulton County Stadium was called "Atlanta Stadium" until 1976. The club level seats were well over 400 feet from home plate. Torre also hit the first home run of any kind at the stadium that season. Here's his 1967 card. Check out those straight eyebrows!

This date in baseball history: I attend my first ever opening day game in person. I'm leaving by bike right after this post to go freeze in the upper deck at Wrigley. Go Cubs!

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

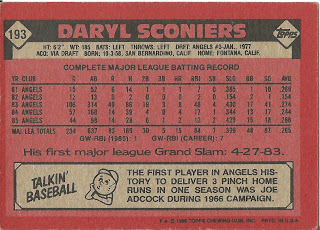

#193 Daryl Sconiers

Card thoughts: I never liked this card. Sconiers’ face, with that wispy mustache, always looked to me to be half finished, somewhat ethereal. This is Sconiers’ last card.

The player: People forget sometimes how integral cocaine use was in the upper echelons of our society in the early 80s. Baseball was not unaffected by this tend, and Daryl Sconiers was one of its victims.

Sconiers was a hitting machine in the minors, winning a batting title in the Texas League (.370) and hitting .354 in the Pacific Coat League in 1981. After hitting over .300 yet again the next year at AAA (interspersed with a knee injury), Sconiers was brought up to the big club and hit .154 in limited action.

Unfortunately, future hall of famer Rod Carew was blocking Sconiers at first, so he took on a utility role for the 1983 season. He hit well, hitting 8 home runs and 46 runs batted in in only 314 at bats. Sconiers had a good chance in 1984 to get more playing time, as Carew was aging fast. But he hurt his back, and only made it into 46 games.

Sconiers was AWOL from much of spring training in 1985. Even his agent couldn’t find him. Apparently, he was on a cocaine binge. Eventually, Sconiers appeared in camp, and entered a substance abuse program. He did play that season, but only got into 44 games while hitting .286. Sconiers season was shortened by drug abuse and injuries once again to his back and knees.

This would be the last look Sconiers would get in the majors, although he continued on in the minors until 1991, in the Angels and White Sox systems, at one point even playing with an independent team in A-ball (the same team fellow suspected drug abuser #158 Derrel Thomas left in a huff) . Even while in the minors, he found it hard to keep out of trouble. He was arrested in connection with an armed robbery in his hometown of San Bernardino, California in 1988 while with the White Sox AAA club.

Reportedly, Sconiers never was able to completely kick his cocaine addiction and is homeless on the streets of his hometown.

Rear guard: This was no doubt Sconiers' last grand slam. His "first" slam came against the Tigers' reliever Bob James and drove in #62 Bob Boone, Juan Beniquez, and Rod Carew. #55 Fred Lynn also hit a grand slam in this game, where the Angels won 13-3.

This date in baseball history: In 1985, the League Championship Series is agreed to be extended to 7 games for the first time.

Monday, April 2, 2012

#192 Milt Wilcox

Card thoughts: Milt Wilcox: tortured mound artist, in a downbeat pose, no doubt contemplating the perfidy of Rogozhin, Nastasya, and Ganya in The Idiot.

The player: Wilcox found early success as a member of the Reds, spent years as a hard-throwing, ineffective pitcher, and finally became a good pitcher in his 30s as result, ironically, or his arm troubles. His out pitch was a devastating forkball, but many said that he became a better pitcher after learning the spitter from Gaylord Perry. But Wilcox owed most of his career success to his stubbornness and determination, as well as his propensity to brush back batters. Wilcox was also suspicious—he always threw the same 8 warm-up tosses and ate blueberry pancakes the day before a start.

Wilcox initially made his mark with the Reds. Arriving in Cincinatti at the tender age of 20, Wilcox went 3-1 with a 2.42 Era to close out the season. In the playoffs, he became the youngest pitcher to ever win a post season game, defeating the Pirates in a three inning relief appearance of Tony Cloninger. He was not as lucky in the World Series, when he took a loss to the Orioles, when he gave up two runs in the fifth inning in the second game. Wilcox was back the next season, but he clashed with manager Sparky Anderson and catcher Johnny Bench over pitching style, as so was shipped off to the lowly Cleveland Indians for Ted Uhlaender.

With the Indians, he was made a full time starter for the first time, but he didn’t take well to it, posting records of 7-14 and 8-10 in his first two seasons with the team. Wilcox hurt his arm in the latter season, which caused his velocity to drop. The Indians were unwilling to trust him any longer in the rotation, so he was banished to the bullpen in 1974, where he pitched marginally better.

Now a sore-armed, ineffectual pitcher, Wilcox was unceremoniously shipped to the Cubs for Brock Davis (a 30-year-old minor leaguer) and closer Dave LaRoche, who was really good for the Indians. Wilcox was reduced to a mop up role, and was sent to the minors on a “deal” with manager Jim Marshall, who promised that he would be back up in six weeks if he “shaped up.” Six weeks elapsed without a call, and Wilcox had to convince the GM to let him come back up. The next season, he wasn’t even that lucky, as he was busted down all the way to AA Wichita as the emergency starter and mop up man. He was thought so little of, he was loaned out to the Tigers AAA club when that team had trouble filling out their starting rotation. The Evansville club eventually traded some old uniforms (!) for Wilcox, and he was now Tigers property.

Wilcox finally learned how to pitch in Detroit. Due to his arm injury, he had to rely on guile rather than power to get pitchers out. He was a much better guile pitcher than power pitcher. Wilcox would begin a string of seasons between 1978 and 1984 where he won more than 10 games and had an above .500 record. In 1981, Wilcox placed in the top 10 in wins with 12. Wilcox almost pitched a perfect game in 1983, but White Sox pinch hitter Jerry Hairston singled just past the outstretched glove of #20 Lou Whitaker. Wilcox, upset, reportedly walked the streets of Chicago all night long. Here’s Ernie Harwell’s call of the final inning.

But his best season was the Tigers 1984 World Series winning season when he went 17-9 with a 4.00 ERA. Wilcox established a record that year by being the first pitcher in baseball history to spend an entire season in the starting rotation without a complete game. This record is now the norm for starters. Wilcox also found time to record some commercials, showing better than usual polish in the spots.

Arm soreness returned to Wilcox during the season shown on this card, and he started only 8 games and won only 1. The Tigers released Wilcox at the end of the season, and he signed with the Mariners. A terrible year followed where he went 0-8 in 13 starts, with a 5.50 ERA. This convinced Wilcox to retire.

In his retirement, Wilcox has won a couple of “air dog” contests, you know those weird tourney’s where dogs jump off a diving board. He even runs his own air dog organization.

Rear guard: Little did Wilcox know that his solitary win in 1985 would be his last. He lasted only five innings against the Rangers, but didn't give up a run.

This date in baseball history: Mets manager Gil Hodges suffers a fatal heart attack after playing a round of golf in 1972. He will be replaced by another New York baseball legend, Yogi Berra.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)